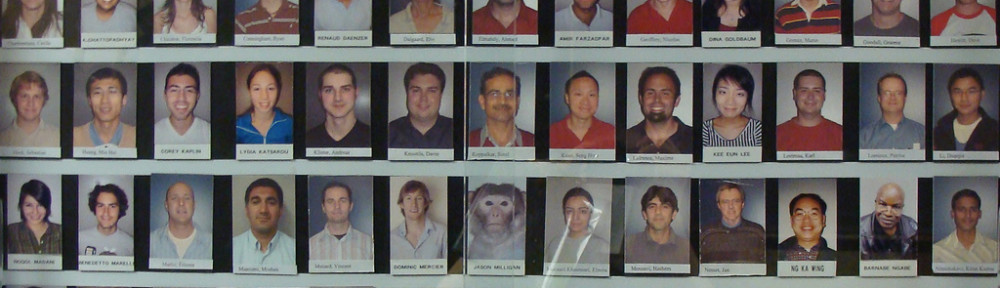

Med students at a #blacklivesmatter die-in at Stanford University. There is a planned die-in across the country on April 4. (Image source: David Purger, PhD, Stanford University. Used with permission.)

Editor’s Note: This post is submitted by Luciano Lima, a doctoral student at the Illinois School of Professional Psychology at Argosy University, in Chicago, Illinois. APAGS does not have an official position on this event, and takes no responsibility for any actions that may result from one’s independent decision to participate.

Open Letter to Graduate Students in Psychology

Over the past few years this country has experienced an upwelling of racial strife resulting from the deaths of numerous black men, boys, and women at the hands of police officers. In response, medical students throughout the country staged a coordinated nationwide Die-In protest against racial bias and violence, which included over 90 medical schools and thousands of students. I observed their activities with admiration and thought to myself, “Why can’t we do that? The reasons provided by the medical students for their protest are just as applicable to graduate students in psychology:

“Racial bias and violence are not exclusively a problem of the criminal justice system. As we have seen in Ferguson, Mo., New York, and countless other places, bias kills, sickens, and results in inadequate healthcare. As medical students, we must take a stand against the oppression of our black and brown patients, colleagues, friends, and family. By standing together at medical schools nationwide, we hope to demonstrate that the medical student community views racial violence as a public health crisis. We are#whitecoats4blacklives.”

Racial bias causes damage not only to the physical, but also the mental health of our clients. We are intimate witnesses to the psychological harm that results from police violence and racial profiling—from the teenager who is unjustly stopped and searched on a routine basis merely for possessing the wrong skin color, to the families, loved ones, and communities traumatized by senseless killings.

In the APA Ethics Code, a guiding principle of our profession is promoting the welfare and protection of the individuals and groups with whom psychologists work. The code also calls on psychologists to “respect and protect the civil and human rights” of our clients. When the welfare of our clients is jeopardized by racial discrimination, we are called to stand up and seek justice on their behalf. Towards this end, we are calling for a coordinated nationwide Die-In demonstration of graduate psychology students and others who are passionate about this cause.

The nationwide Die-In of graduate psychology students will be on Monday, April 4, 2016, the anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

We call on fellow students to take up the torch and organize Die-ins on their respective campuses. The Chicago branch of the Die-in will be meeting at Daley Plaza (50 W Washington St, Chicago, IL 60602) at exactly 5 p.m., central time. We will lay together in silence for 16 minutes, each minute representing one of the bullets fired into Laquan McDonald. Please bring signs and dress for the weather!

We have created a Facebook event page to help coordinate our activities.

We call on student leaders to spread the word throughout their programs, so that we can make a powerful statement of our values and vision for the future. Also, please share this letter on social media and email your friends and colleagues to help get the word out.

Your Fellow Students,

#psychologists4blacklives

For additional questions please contact Luciano Lima and Keisha-Marie Alridge.

By Kala J. Melchiori, PhD (Asst. Professor of Psychology, James Madison University)

By Kala J. Melchiori, PhD (Asst. Professor of Psychology, James Madison University)