For Third-Year Students: This year is all about knowing when to plug in and when to unplug. With two years under your belt, you can not only identify your strengths but are also likely to be able to identify the people and places that make you stronger. Make this year about capitalizing on the connections you’ve made, and don’t forget to add a little something new along the way!

(Source: GotCredit on Flickr; some rights reserved)

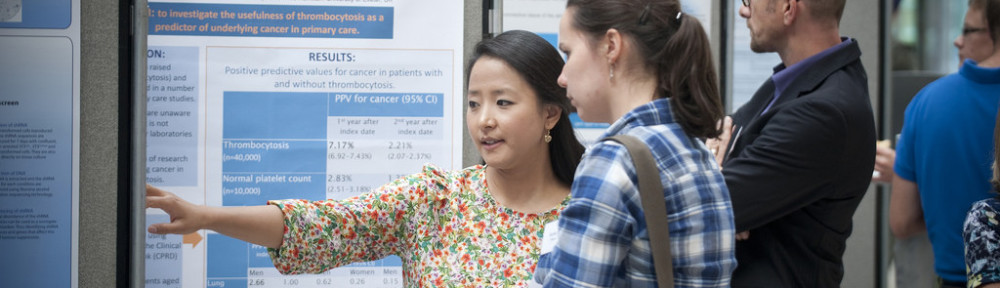

Develop support systems.

After two years in your doctoral program you are likely to have been exposed to both happy and more trying moments. In those moments you’ve probably taken note of who was with you during those easy and hard times, and how they contributed to your experiences. Remember those people, and keep in touch with those who make you the happiest. Some of these people might be in your own research lab or weekly seminar. Others might be friends of friends who are not in graduate school, but manage to force you out of your apartment on a Saturday night on a strict “no-thinking-about-your-research” policy. Whether in your cohort or off-campus, these are the people who get you through. Know who they are and make time to be with them.

Take a vacation! Or just temporarily vacate.

Take a moment, or get moving…either way find time and space away from work (Source: Willemvdk on Flickr; some rights reserved)

Sometimes a great getaway is just a bike ride rather than an expensive plane ticket, away! Remember to bring along your important people and hit the road. (Source: Kamal Zharif on Flickr; some rights reserved)

It is likely that limited finances and long hours of studying, teaching, data analysis, or conference preparation will all be viable reasons for not taking the breaks we would like to take. It is this writer’s opinion, however, that you don’t need to be 100% settled in life to take a 100% rest. When and however you can, build in time to get away from your program. Getting away does not necessarily need to look like everyone else’s vacation. There are, however two requirements: (1) no checking email (yes, I said it); and (2) leaving the vicinity that you currently live or go to school in. As long as your mind is not on work and you are off the grid, you are resting. For example, even if you do not have the option of going on a trip that requires spending money and a passport, you can still pool your options for going someplace new—even if it is only for a weekend.

Some doctoral students prefer to save for a one-to-two week trip. Others may benefit more from shorter weekend trips. Whichever way you travel, allow yourself the escape. The more able you are to take a break, the easier it will be to look forward to getting back to work with a clear head.

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of a 4-part series. View part 1, dedicated to the first-year graduate school experience, and part 2, dedicated to the second year.

Approaching a new academic year is a lot like New Year’s Eve: It offers much of the same excitement, anticipation and hopes of good fortune that a new calendar year has come to symbolize. It’s also a time when we develop resolutions, consciously or not. We want to do well in our programs, we want the best for our clients and students, we want successful (and publishable) research and we want to be part of a thriving profession.

Approaching a new academic year is a lot like New Year’s Eve: It offers much of the same excitement, anticipation and hopes of good fortune that a new calendar year has come to symbolize. It’s also a time when we develop resolutions, consciously or not. We want to do well in our programs, we want the best for our clients and students, we want successful (and publishable) research and we want to be part of a thriving profession.