Guest columnist: Craig

Describe an instance where you were “forced” to choose or represent one identity over another. How did you negotiate this instance? What did you learn from this experience?

As a life-long stutterer, I am often faced with a dilemma every time I speak with someone in both my personal and professional life: Do I align with my identity as a stutterer by speaking with repetitions, prolongations, and blocks, or do I maintain my fluency by speaking in a coherent, smooth, and consistent manner? This quandary is cognitively and emotionally present in all contexts that involve spoken language. Magnifying the difficult decision is the stutterers’ often keen ability to “hide” his dysfluency. Unlike other apparent identities, stuttering is more covert, often hidden under the guise of fluent speech. Thus, during conversations with others, I often ponder three questions: Do I disclose my stutter? Will the other person figure out I stutter? How long can I maintain fluent speech?

Much to my dissatisfaction, I will often conceal my stutter, in order to align with the identity of being a nonstutterer. This “false” identity is accompanied by a lack of disclosure, embarrassment and shame, following a concerted effort to talk in a manner that involves absolutely no repetitions, blocks, or prolongations. I recall one instance in which I chose to hide my stutter from a 14-year old male client. The client asked, “Mr. Craig, do you stutter?” I replied, “Um, no, I don’t. Sometimes I get caught on my words.”

I chose this response to avoid any discussion that may have revealed my true identity as someone who stutters. I quickly changed the subject without hesitation. In essence, the opportunity to be vulnerable with my client by revealing my own imperfections (stuttering) was quickly shut down to avoid my embarrassment and shame.

I learned an important and valuable lesson from this encounter. Being vulnerable with another person implies uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure. However, it also provides an opportunity to forge deep bonds of affection toward another. I lost this opportunity with my 14-year old client. As I reflect on this experience, I realize that it is only through my imperfections and fallibility that I can be an effective therapist. This means that I may stutter when I talk with clients. It may take me a few more seconds to utter a sentence. I, like my clients, am not perfect. I mistakenly believed in that moment of response that my ability to maintain fluent speech was connected with my competency as a therapist. I now realize that this was a great misperception—to be an effective therapist means being comfortable with my own vulnerability. This means befriending my stutter with an open heart and genuine curiosity when it emerges in session. By doing so, I subtly invite my clients to also be vulnerable with their pain and suffering. After all, at the end of each session, both therapist and client are human, all too human.

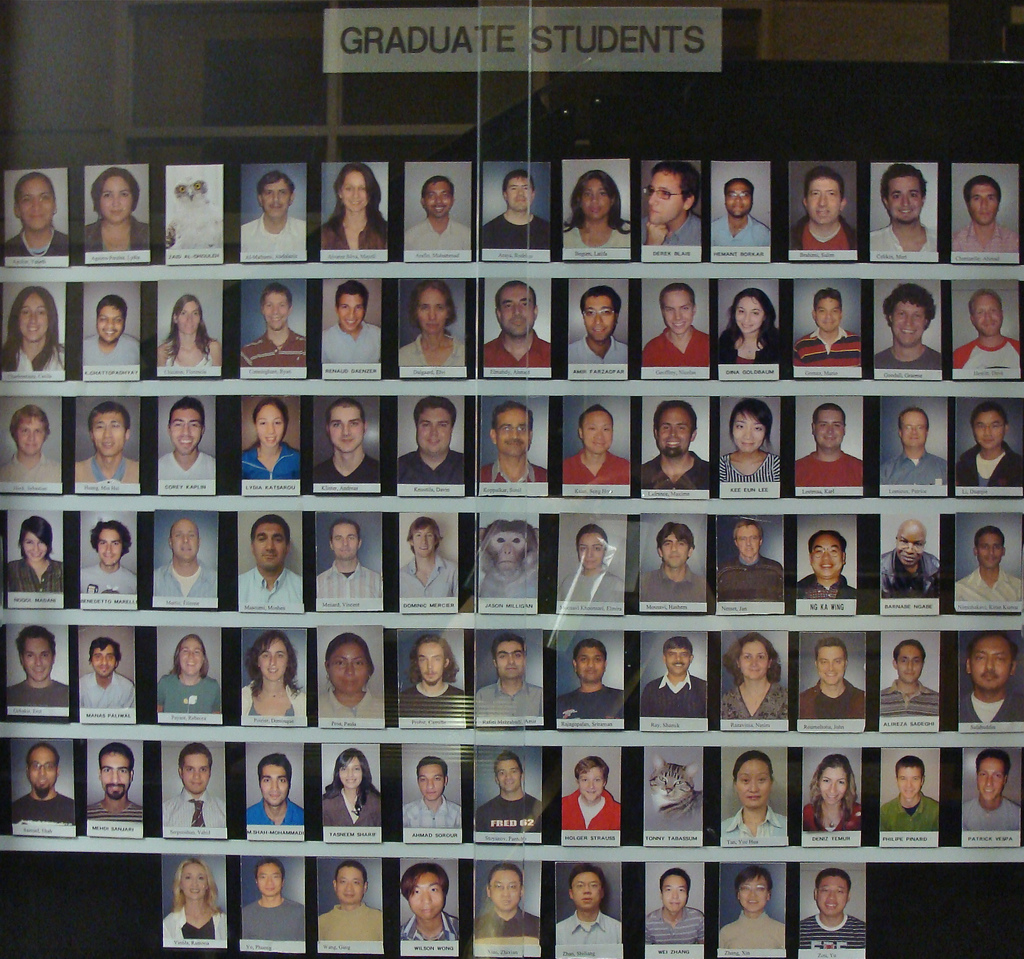

This column is part of a monthly series highlighting the experiences of students and professionals with diverse intersecting identities and is sponsored by the APAGS Committee on Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity and the Committee for the Advancement of Racial and Ethnic Diversity. Are you interested in sharing about your own navigation of intersecting identities in graduate school? We would be happy to hear from you! To learn more, please contact the chair of APAGS CSOGD: Julia Benjamin or APAGS CARED: James Garcia.

Start your fourth year in the summer.

Start your fourth year in the summer.

Directorate • January 13, 2016

Directorate • January 13, 2016