Recently, I had been trying to come up with creative ways to help my students link concepts from class to the real world. Improving learning is one connection. But there are many others, such as how we might frame an advertisement to help it sell, or how we can improve procedures in the criminal justice system to avoid false convictions – like Steven Avery’s first conviction. (The many who watched Making a Murderer have probably thought a lot about this connection to cognitive psychology, possibly without realizing how much of a role it plays!) Anyway, I decided to create an assignment requiring my students to interact with one another and make connections with popular psychology-related articles on Twitter. The first step was creating a Twitter profile for myself, and building it up with psychology-related tweets.

Recently, I had been trying to come up with creative ways to help my students link concepts from class to the real world. Improving learning is one connection. But there are many others, such as how we might frame an advertisement to help it sell, or how we can improve procedures in the criminal justice system to avoid false convictions – like Steven Avery’s first conviction. (The many who watched Making a Murderer have probably thought a lot about this connection to cognitive psychology, possibly without realizing how much of a role it plays!) Anyway, I decided to create an assignment requiring my students to interact with one another and make connections with popular psychology-related articles on Twitter. The first step was creating a Twitter profile for myself, and building it up with psychology-related tweets.

One random night, I saw that Yana was tweeting many messages to a lot of different Twitter handles. It turns out Yana had been feeling guilty that she wasn’t doing more to reach out to the community with her work on improving study strategies. Somewhat impulsively, she tried searching “test tomorrow” on Twitter, and realized that TONS of students were tweeting about upcoming exams. Many students were tweeting about being unprepared, not knowing how to study, or being unable to concentrate.

So, Yana started tweeting advice and encouragement to the students: wishing them luck on their exams, asking them what strategies they used to study, and whether they’d tried practice questions or writing out everything they knew on the topic from memory. I thought it was such a cool idea that I decided to join in. I suggested we start using the hashtag #AceThatTest, and overnight that hashtag had turned into our joint Twitter account: @AceThatTest. That was January 22nd, 2016.

Since then – in under a month – we have gained almost 700 followers on Twitter, tweeted well over 2,000 times, hired a student intern, made a website with a blog (learningscientists.org), been asked to help out with a book on learning, and forged many new connections with researchers and educators around the world. The project really took off in ways that I think neither of us had anticipated! The passion we both bring to the project comes from our mutual frustration with the lack of communication between science and educational practice.

We want to improve communication between the various educational experts. Education is an extremely important topic, and we believe that there are many experts in this realm, each bringing an important perspective that can serve to improve education. Teachers who have been practicing in the classroom for years are experts. Students, by the time they graduate high school, and may be considering entering into higher education, have 13 years of educational experience under their belts, and could be considered experts. Professors, like Yana and myself, who both research learning (sometimes in the lab, sometimes in live classrooms) and teach undergraduate students in our own classrooms are experts. Professors who are working with teachers in training in institutions of higher education are experts.

If you have an “it takes a village” mentality, like we do, then the idea of having so many experts with diverse experiences and perspectives is extremely exciting. No one person can solve every problem that comes up, but a diverse group has serious potential to get things done. Unfortunately, many of these groups are not communicating with one another as much as we believe they should be. The situation is not entirely dissimilar from the schism between research and practice in clinical psychology. In an ideal world, researchers would clearly communicate their findings and make them easily accessible to practitioners. Meanwhile, practitioners would communicate any practical concerns they have with implementation to inform further research. Yet instead of this type of symbiotic relationship, there is a strained relationship between clinical practice and clinical research, and the lines of communication are not as open as they should be, and need to be if we want clinical psychology to be maximally beneficial for the profession and the public as a whole. Clinical psychologists know this, and have been addressing the problem; there have even been special APA Convention programs and even special journal issues to address the lack of communication.

The same problem occurs in education – communication is simply not open, and it’s time for the many educational experts to address this. We have to talk to each other if we want to improve education. It seems to us that we can’t complain about a lack of communication while keeping our heads down in our own silos. For this reason, Yana and I started the Learning Scientists community.

Please help us spread the word, and open lines of communication between all education experts. There are many opportunities for you to get involved: Tell colleagues outside of psychology about this work, follow us on Twitter and tweet at us, comment on our blog, or even write a piece on something you’re passionate about and send it to us. You can get in touch with us through our website via our “contact us” tab, or on Twitter @AceThatTest.

About the authors:

About the authors:

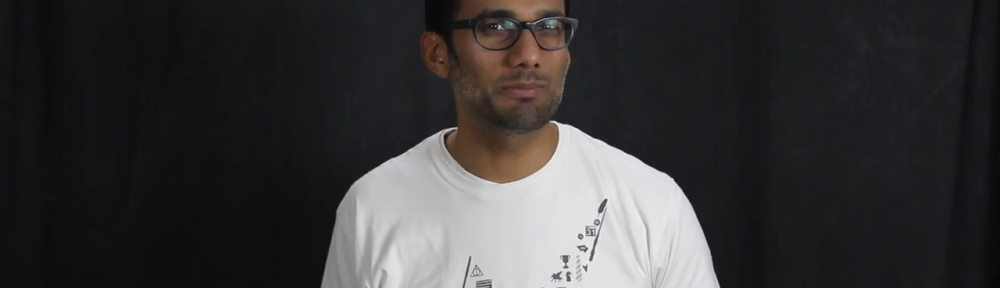

Megan Smith is an Assistant Professor in the Psychology department at Rhode Island College. She received her Master’s in Experimental Psychology at Washington University in St. Louis and her PhD in Cognitive Psychology from Purdue University. Megan’s area of expertise is in human learning and memory, and applying the science of learning in educational contests.

Megan Smith is an Assistant Professor in the Psychology department at Rhode Island College. She received her Master’s in Experimental Psychology at Washington University in St. Louis and her PhD in Cognitive Psychology from Purdue University. Megan’s area of expertise is in human learning and memory, and applying the science of learning in educational contests.

Yana Weinstein is an Assistant Professor in the Psychology department at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. She received her PhD in Psychology from University College London and had 4 years of postdoctoral training at Washington University in St. Louis. The broad goal of her research is to help students make the most of their academic experience.

Yana Weinstein is an Assistant Professor in the Psychology department at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. She received her PhD in Psychology from University College London and had 4 years of postdoctoral training at Washington University in St. Louis. The broad goal of her research is to help students make the most of their academic experience.

Together they co-founded the Learning Scientists (@AceThatTest on Twitter) to make scientific research more accessible to students and educators.