From Psychology Benefits Society, A Blog from the APA PI Directorate • November 6, 2015

By Gabriel Twose (Senior Legislative and Federal Affairs Officer, APA Public Interest Government Relations Office)

Do you think that the field of psychology has anything to say about the minimum wage? In a recent article in American Psychologist, Laura Smith of Columbia University argues that psychology has much to contribute. Psychological research contributes to our understanding of poverty by highlighting its developmental and health risks for low-income Americans, and how stereotypes about poverty affect that population.The Facts about the Minimum Wage

Do you think that the field of psychology has anything to say about the minimum wage? In a recent article in American Psychologist, Laura Smith of Columbia University argues that psychology has much to contribute. Psychological research contributes to our understanding of poverty by highlighting its developmental and health risks for low-income Americans, and how stereotypes about poverty affect that population.The Facts about the Minimum WageThe federal minimum wage in the United States was established in 1938 as part of the Fair Labor Standards Act, aiming to ensure “a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work.” It reached its peak buying power in 1968, but has failed to keep up with inflation. The minimum wage was raised to $7.50 per hour in 1999, which is where it stands today. This is far from a living wage – it is not enough to lift a full time worker with a child above the poverty line. Although a number of states tie their minimum wage to the cost of living, the federal government has not instituted such an index.

Psychological harms of poverty

Poverty and economic adversity can be difficult environments. Substantial psychological evidence has outlined the potential harms that can accrue. For example, low-income children and adults are more likely than those living in more affluent circumstances to be at risk for developmental, emotional, and behavioral disorders and worse academic outcomes, with negative implications for success later in life.

Marginalization and exclusion

Psychological research has also looked at other facets of the debate around the minimum wage. Stereotypes about individuals shape others’ reactions to them and opportunities provided to them. We know that the poor are often stereotyped as lazy and stupid, and both politicians and the general public tend to ignore the structural factors that create and perpetuate their circumstances. Low-wage workers are often treated worse than other workers; you can probably think of examples in your own life, as you’ve seen how people can speak to fast-food workers, janitorial staff, or manual laborers. Dr. Smith cites a study in which participants rated applicants for a position in a parent-teacher organization; when the candidate was described as working class, she was rated as cruder, more irresponsible, and less suited for the position. These kind of biases and stereotypes, often unconscious, can lead to marginalization and social exclusion. This exclusion can make it more difficult to get a job, and has additional harmful effects; excluded people tend to behave more aggressively, make more high-risk, self-defeating decisions, and score worse on logic and reasoning tasks.

Policy Solutions

Dr. Smith points out that several cities have already begun experimenting with increased minimum wages in order to lift workers out of poverty, including San Francisco, CA, Seattle, WA, and Santa Fe, NM. Additionally, there are a number of relevant federal bills, several of which have been supported by APA.

- Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) and Representative Bobby Scott (D-VA) have introduced legislation that would raise the minimum wage to $12 an hour by 2020 ( 1150/H.R. 2150).

- Senator Bernie Sanders (D-VT) and Representative Keith Ellison (D-MN) have called for an increase to $15 an hour ( 1832/H.R. 3164).

- Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) introduced the Fair Employment Opportunity Act of 2014, which would prohibit employers and employment agencies from discriminating against unemployed job-seekers by refusing to consider them for employment. Although this bill was not passed, it has been incorporated into the recently introduced Jobs! Jobs! Jobs! Act of 2015 (R. 3555).

Get involved!

Psychological research has an important role to play in the conversation around the minimum wage, explaining both the negative effects of poverty and the ways in which we marginalize the poor, deeming them unworthy of our help. The minimum wage is a natural focus for psychologists’ advocacy, and we encourage you to get involved. A great way to do this is to sign up for APA’s Federal Action Network, joining 123,000 members and affiliates in raising psychology’s voice as one.

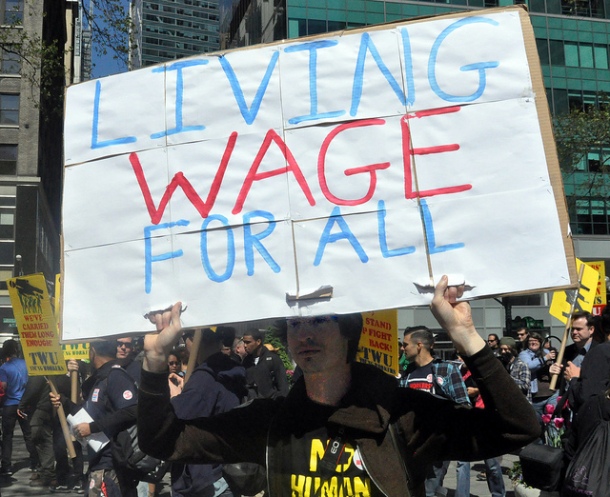

Image source: Flickr user Michael Fleshman on Flickr, under Creative Commons