Editor’s note: This post coincides with LGBT Health Awareness Week, March 23-29, 2014. It was written by Julia Benjamin, a member of the APAGS Committee on LGBT Concerns. Stay tuned for the second post in this series later this week.

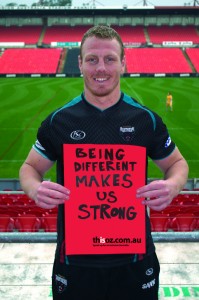

Are we as supportive of LGBT players in sports as we could be? (Source: “Luke Lewis, Penrith Panther and NSW Blues” by Acon Online on Flickr. Some rights reserved.)

When members of the Westboro Baptist Church protested openly gay University of Missouri football player Michael Sam, over one thousand Mizzou students formed a human chain around campus to support Sam and block the protest. This show of solidarity stands in contrast to the traditional locker room culture of homophobia that was recently highlighted by the bullying of former Miami Dolphins player Jonathan Martin. In light of this tension between heteronormative locker room culture and shifting national levels of LGBTQ acceptance, what are the health implications of identifying as both a student athlete and as LGBTQ?

Meyer’s theory of minority stress posits that LGB individuals experience more mental illness due to constant environmental prejudice. A recent national study supports this theory; LGBTQ individuals who live in communities with negative attitudes toward them were found to have shorter lifespans. In particular, deaths associated with stress, like suicide and cardiovascular disease, were higher for LGBTQ individuals living in high-stigma areas.

Minority stress may be especially high for student athletes. According to Campus Pride’s 2012 LGBTQ National College Athlete Report, twice as many LGBTQ student-athletes reported experiencing harassment as their straight peers. They also reported experiencing a more-negative overall climate that was detrimental to their academic success. Additionally, studies indicate that stress may be stronger for male-identified LGBTQ students because male student athletes have been found to hold more negative LGBTQ attitudes than females.

However, there is cause to be optimistic about the future of the mental and physical health of LGBTQ student athletes:

- In the past few months, several college athletes have received support after publicly coming out, including All-American University of Missouri defensive lineman Michael Sam, Notre Dame tennis player Matt Dooley, and Drew University baseball captain Matt Kaplon.

- Many college communities and athletic departments are becoming more accepting of LGBTQ individuals. New research has indicated that a majority of college coaches and athletic trainers hold positive attitudes toward lesbian and gay athletes.

- National organizations like Go!Athletes, Outsports, and You Can Play work to support and empower gay student athletes.

- Acceptance of gay athletes appears to be infusing professional sports as well. In a recent ESPN poll of NFL football players, 86% indicated that a player’s sexual orientation did not matter to them and 75% said that they would be comfortable showering around a gay teammate.

- Studies show that knowing someone who identifies as LGBTQ leads to greater acceptance.

As more college athletes come out and as campus communities encourage awareness, support, and inclusive language and policies, it is inevitable that college locker rooms will become healthier and safer spaces for all athletes.

Following our recent post on racial microagressions, we found some fascinating articles by Dr. Kevin Nadal (Associate Professor of Psychology, John Jay College of Criminal Justice – City University of New York) on microagressions that affect LGBTQ people. Read about

Following our recent post on racial microagressions, we found some fascinating articles by Dr. Kevin Nadal (Associate Professor of Psychology, John Jay College of Criminal Justice – City University of New York) on microagressions that affect LGBTQ people. Read about

When I woke up and read the email that I didn’t match, I was filled with anxiety, self-doubt, and hopelessness. Where had I gone wrong? What more could I have done? I prepared for Phase II and submitted more applications. But with so many students vying for so few placements I was not surprised when I didn’t match again.

When I woke up and read the email that I didn’t match, I was filled with anxiety, self-doubt, and hopelessness. Where had I gone wrong? What more could I have done? I prepared for Phase II and submitted more applications. But with so many students vying for so few placements I was not surprised when I didn’t match again.