Many graduate students in clinical, counseling and school psychology programs are preparing applications to internship positions across the country this fall. The internship component has been a requirement to earn a doctoral degree in these programs for decades. And every year the American Psychological Association’s Commission on Accreditation (CoA) collects data on students in accredited doctoral and internship programs.

Let’s have some fun with those data!

The first chart shows the mean and standard deviation of stipends from APA accredited internships from 1998 to 2012. Click the chart to magnify it:

Since 1998, the mean stipend for clinical, counseling, and school psychology interns has increased steadily. In fact, the stipends one standard deviation below the mean have increased by almost $5,000. (Source.)

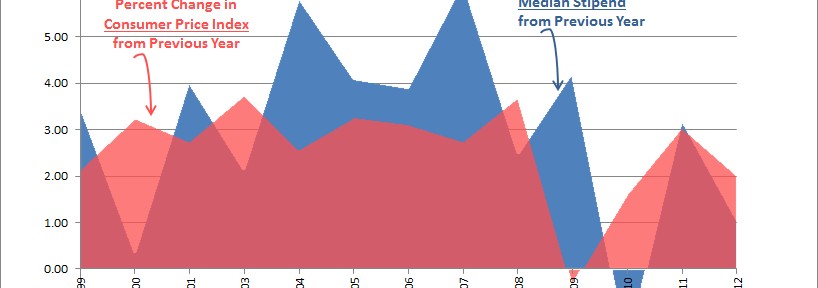

While internship stipends have generally been increasing, do they cover the cost of living? My second chart presents the percent change in the median internship stipend and the percent change in the consumer price index (CPI) from year to year:

As you can see, the percent change in median stipend amount is greater than the percent change in CPI for some years but not others. It seems that although many stipends cover the cost of living, the percent change in stipend amounts is not always in pace with this marker of inflation (source). The good news? The 1998 mean intern stipend, adjusted for inflation, still beats the amount one would expect to earn in adjusted dollars for 2012 by nearly $1,500.

The percent change in stipend amounts is not always in pace with this marker of inflation.

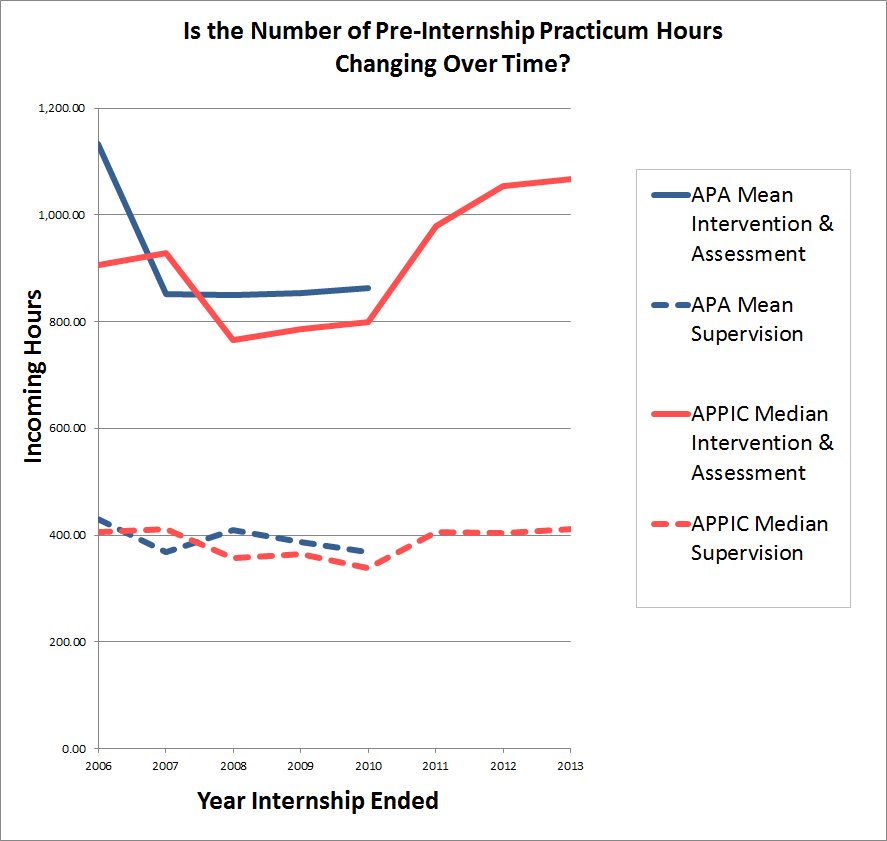

Beyond stipends, I decided to look at the trends in practicum hours reported by internship applicants. In particular, I wondered if the internship crisis was leading to greater accumulation of hours by students who desire to appear more competitive. This third chart shows practicum hours of applicants from 2006 to 2012, broken into supervision and assessment/intervention categories:

It appears that the trends in supervision and in assessment/intervention hours are similar between the APA mean (blue) and APPIC median (red) hours. If we look at the most recent data, it appears that median hours are increasing over time. Students applied to internships with 18% more intervention/assessment hours in the eight years between 2006 and 2013.

It appears that median hours are increasing over time.

(Sources: Mean practicum hours are reported by APA, though public release of data in this area ceased in 2010. Median hours are reported by the Association of Psychology Postdoctoral and Internship Centers, or APPIC. It is important to note that APA accredits some doctoral and internship programs, almost all of which send students through the APPIC national match. APPIC data report students from accredited and unaccredited doctoral programs vying for accredited and unaccredited internships.)

Any thoughts on the data I presented? Are you surprised by the trends? Do any possible interpretations come to mind? I welcome you to comment on this post!

This spring, a group of APAGS members recorded a

This spring, a group of APAGS members recorded a