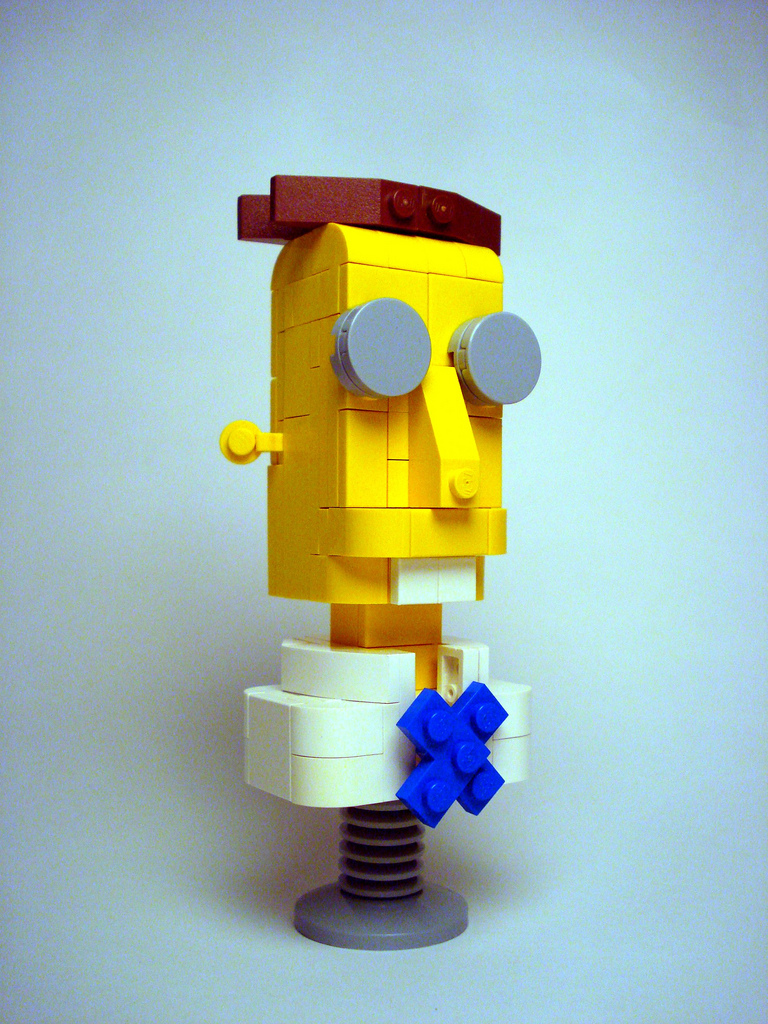

My heart belongs to a beagle. And considering his desire for attention/affection, he will be delighted to know he’s the topic of discussion in this post.

My dog’s name is Beckett and my husband, Craig, and I rescued him three years ago this summer. As a graduate student in psychology, Beckett is a vital facet of my self-care. He is sweet, chill, and smart as heck. He loves belly rubs, long walks, and baby carrots. He also loves me unconditionally and serves as my unofficial therapy dog. I’m pretty much obsessed:

I should mention Beckett is spoiled. Spoiled. Rotten. I mean, his bed is nicer than ours. I dare say he’s unabashed by the steady stream of attention, grain-free treats, and seasonal collars. He comes by it honestly.

Being strong-willed/spoiled, Beckett can also be naughty as all get out. I’m serious. Within the last month, he has knocked over trash cans (thanks, dude), escaped from my parents backyard by climbing poultry wire (three times!), marked his territory on a girl’s backpack at the park (#mortified), and ate seven dyed Easter eggs.

“You’re welcome,” said the hound to the Mel.

Currently (and until we are 80+ years old), my husband and I are both students in the counseling psychology doctoral program at WVU. Despite his #beaglemonster ways, Beckett is a constant source of joy for us. That said, and nothing personal to my baby boy, he’s an additional responsibility on top of our academics, research, clinical work, finances, and jobs. In this post, I wanted to provide my perspective on having a dog in graduate school. Frankly, my perspective is one of many but if you’re considering adopting a pet in graduate school, you may find the challenges/benefits below helpful.

Side note, they teach us in psychology to be aware of our biases. Therefore, I will own up front that my opinions about pets will always lean toward the benefits.

Challenges (“Growth Edges,” as we say in psychology) of Pet Ownership:

- Time commitment – feeding, quality time/attention, taking them out, cleaning cages, training, etc.

- Financial responsibility – vet visits, annual exams, nails, baths, supplies, adoption fees, etc.

- Pets, like humans, can sometimes be on “bad behaviors” (as Craig says) and need to lose some privileges (e.g. my dog)

- Much more difficult to coordinate care of the animal if you don’t have someone to help you (= me during my first year when Craig and I lived 10 hours apart)

- Can’t just pick up and leave, always need to arrange accommodations (which can be pricey)

- Minor annoyances – dog takes forever to do his business, dog wants to sniff EVERYTHING, dog refuses to do his business in the rain/sleet/snow, dog fakes an injury when owner makes him go out in the rain/sleet/snow, etc. (not that Beckett would ever commit any of the aforementioned misdemeanors.)

- The answer to, “Did I turn off the straightener?” becomes more important

- Losing a pet is so hard, I know this from personal experience

- Dog may pee on backpacks (ugh)

Benefits of Pet Ownership:

- The feeling of unconditional positive regard (see what I did there?) you receive from loving a cuddly (or scaly, fishy, feathery, etc.) being

- Promote self-care and wellness

- Provide entertainment/laughter

- Help you keep a routine

- Have someone to binge-watch Unbreakable with Kimmy Schmidt and Workaholics with regardless of the time/day

- Can motivate you to stay active if your pet enjoys walks

- Companionship/loyalty

- Keep your feet warm

- Can assuage feelings of loneliness/isolation

- Always have someone to talk to even if you’re just talking to yourself

- Can promote better time management (though I still feel I’m always running from one thing to the next)

- Can cause you to be less “me-focused” in graduate school

- Great distraction for long paper writing (cough, dissertation, cough, cough)

- Owning an animal can be a solid/go-to topic of conversation (e.g. this post)

- Socially acceptable excuse to take/post lots of pictures on social media

- Can connect you to a fun/supportive community of fellow helicopter parents (e.g. the dog park)

- Potentially rehabilitate an animal (you wouldn’t believe it now, but Beckett was skittish, withdrawn, and anxious when we first got him)

- Contribute to positive social change by demonstrating responsible pet ownership

- And of course, the opportunity to rescue

Welp, those are some of my thoughts on pet ownership in graduate school. Above all else, if you’re considering adopting a pet, please make it a thoughtful and responsible decision. And to all my fellow animal lovers out there:

Keep calm and love animals on.

-Mel

Editor’s Note: Melissa Foster is a second year doctoral student from Virginia Beach, VA. She is studying counseling psychology at West Virginia University. Check out her lifestyle blog, Method to My Melness.

![MPj04330550000[1]](http://www.gradpsychblog.org/wp-content/uploads/MPj043305500001-300x199.jpg) Congratulations – you are accepted into graduate school! Whew! It is such hard work to get into a graduate program that it is sometimes hard to remember to take care of yourself once you get there. There are so many things to be involved in, so many things you have to do and learn. And you want to give your absolute best to everything you do.

Congratulations – you are accepted into graduate school! Whew! It is such hard work to get into a graduate program that it is sometimes hard to remember to take care of yourself once you get there. There are so many things to be involved in, so many things you have to do and learn. And you want to give your absolute best to everything you do.

Editor’s note: This post originally appeared in near-identical form in the

Editor’s note: This post originally appeared in near-identical form in the