For Second-Year Students: One year into graduate school, you are likely to meet feelings of adjustment with recognition that you are (somehow) only getting busier. Here are some tips on how to manage your new-found groove while facing even newer challenges and tasks–you can do it! (View Part 1 of this series, dedicated to the first-year graduate school experience.)

Change up where you work.

Studying may not sound like it has much to do with self-care, but after a year in a doctoral program it is as important to continue to stay diligent as it is to make time to play and have fun—this means it is it’s a good idea to match your growing focus with an occasional new discovery, such as a new place to hit the books! There are several gains associated with finding new study spots.

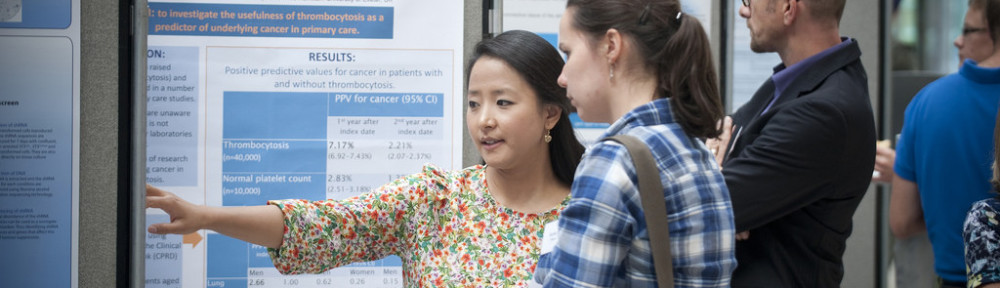

Many students like to find new and interesting places to hit the books. Studying in various locations can help with focus and recall. (Source: Neo II on Flickr. Some rights reserved.)

Research has begun to consistently point to evidence that switching where you work or study can be helpful for your memory, concentration, and performance habits. In addition, finding different places to work familiarizes you with where you live, and can build in organic breaks to your work (for example, a coffee shop closing, the proximity of your local library to a friend’s house or movie theater).

It’s of course important to have a good work space at home and at school, but having other options may allow you to perceive working as less of an inevitable chore and as more of a chance to explore where you live while you develop more flexibility and resilience in your work style. An important disclaimer to this, however, is to be mindful of privacy issues in relation to data, clinical work, and teaching courses!

Begin to shift your focus from “student” to “trainee.”

You are not only a student but a professional in training–don’t be afraid to own it! (Source: University of Exeter on Flickr. Some rights reserved.)

Whether training to become an academic, a public servant, or to work as a clinician, your passion and commitment to your training is your first priority in graduate school. For first year students, this commitment can be daunting to focus on with such primacy amidst moving to a new place, meeting new people, and forging new professional relationships, all while managing a course load. It can feel counter-intuitive (and ultimately can be counterproductive) to try and immediately fully align your priorities to your research, clinical work, or other professional training opportunities during you first year. It may be wise to acquaint yourself with the level of difficulty and expectations around coursework in your doctoral program.

Once you have two terms worth of grades under your belt, however, it is time to make the sometimes awkward shift from over-achieving student to ambitious scholar. This means that caring for yourself while in training will mean caring about what you are there to be trained in.

Let go of perfectionism. Embrace the stumbles, risks, and uncertain steps forward.

By the time you are a doctoral student, it is likely that you are already a high-achieving student, and consequently the tendency may be for doctoral students to initially care more about their performances in their courses than anything else. You should find, however, that your advisors, supervisors, and mentors care about your professional development and scholarship more than they do about your grades. This means it will be up to you to manage coursework with your other responsibilities.A part of this management will mean letting go of the perfectionism common to aspiring graduate students and embracing the stumbles, risks, and uncertain steps forward affiliated with training on the doctoral level.

Uncertainty will not always make you feel good right away but it is far from your enemy. With your sense of self on one side and social support in the other, lean into your training and allow yourself some distance between you and your image of what it means to be the best student—you have bigger fish to fry.

Approaching a new academic year is a lot like New Year’s Eve: It offers much of the same excitement, anticipation and hopes of good fortune that a new calendar year has come to symbolize. It’s also a time when we develop resolutions, consciously or not. We want to do well in our programs, we want the best for our clients and students, we want successful (and publishable) research and we want to be part of a thriving profession.

Approaching a new academic year is a lot like New Year’s Eve: It offers much of the same excitement, anticipation and hopes of good fortune that a new calendar year has come to symbolize. It’s also a time when we develop resolutions, consciously or not. We want to do well in our programs, we want the best for our clients and students, we want successful (and publishable) research and we want to be part of a thriving profession.